Ethical Investing – Whose ethics are we talking about?

It is becoming increasingly common to hear of public and private institutions offloading their ‘unethical’ investments, often in response to demands from their constituents and customers.

In 2017, Auckland Council voted to follow the lead of cities like Paris, San Francisco, and Sydney, and withdraw its investments in companies that produce and extract coal, oil and gas, following years of pressure by environmental activists.

And we regularly hear of those who are working to encourage large investors (e.g. cities, universities, churches, pension funds, museums and other institutions) to adopt a particular ethical or moral position on aspects ranging from gambling to alcohol and fossil fuels.

Of course there’s nothing new about ‘ethical’ investing: individuals and families have long-tailored their portfolios to suit their morals; and specialised equity funds have been available for decades.

What’s changed is heightened public awareness of where our private and public savings are being invested, and increasing recognition that a focus on simply maximising short-term profit is not necessarily the best, or most sustainable approach, over the long term.

Unfortunately, not all investors can agree on what is and isn’t important, meaning the challenge for asset managers is in deciding how to help the maximum number of people without reducing the approach to a lowest common denominator, and thereby making it unattractive to most investors.

Changing our ways

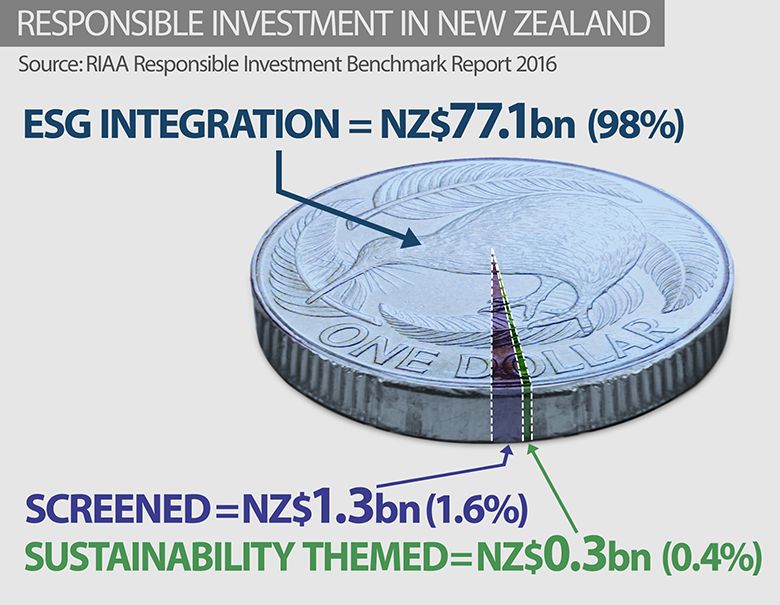

In New Zealand, institutional investors who enjoy good access to executives and boards are able to influence the ongoing behaviour of the companies in which they invest.

For the majority of investors, though, the options for ethical investing are largely limited to simplistic screening processes for pooled funds, such as blanket bans on firms focussed on profiting from activities such as alcohol, gambling, tobacco and fossil fuels.

The trouble with such screens is they are crude and subjective and rarely align fully with the attitudes and behaviours of the investor. By choosing to screen out a particular stock or sector they may be forced to avoid a number of other stocks that they would otherwise happily own.

Alcohol producers and sellers, for example, are often excluded from ethical funds due to the known social harm from their product, yet at last count 80 per cent of Kiwis admitted to having had a tipple in the previous year – a fairly strong indicator that most of them wouldn’t want alcohol production to cease.

Likewise, fossil fuels are now starting to be excluded from specific funds – singling out producers of the fuel that 99 percent of us still use to enjoy the benefits of travel and trade, and alienating those investors who don’t want such a simplistic screening process.

At the same time, the shortcomings of a crude screen can be seen in the example of social media, which has given rise to terrible harassment and bullying, even ‘live murders’, but remains popular with investors and is yet to be the target of any divestment campaigns, or be screened out of any ethical funds.

And even if there were, it’s doubtful investors would give up on social media just because of its ever-present ‘trolls’ – whose actions are arguably quite distinct from the company offering the platform.

Such is the dilemma for those wanting to invest responsibly – if the blanket bans don’t match your own values you may be turned off the idea simply because you don’t want to look like a hypocrite!

A middle ground

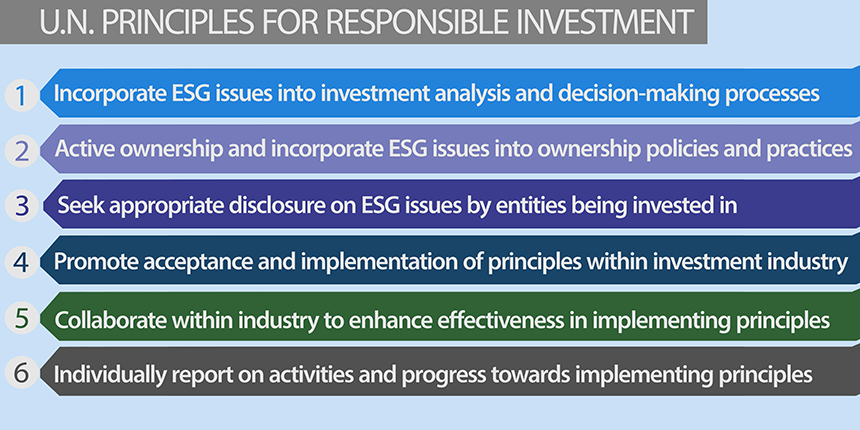

One solution is a more nuanced approach in the form of the Environmental, Social & Governance (ESG) principles that are at the heart of the United Nations’ Principles of Responsible Investing.

Thankfully, as debate over ethical investing intensifies, awareness of ESG principles is growing and the adoption of these features in investment processes is becoming increasingly mainstream.

Contrary to what some activists might tell you, ESG isn’t about slavishly avoiding stocks in a certain industry, or trying to force a particular ethical or moral viewpoint on other investors– rather it’s about incorporating such principles into investment decisions with the goal of improving the long-term interest of markets, economies and ultimately society.

For example, instead of banning investment in alcohol companies, an ESG approach may ensure a company does not have a record of marketing to minors.

Similarly, rather than excluding fossil fuels, an ESG approach might recognise those companies which place greater emphasis on minimising pollution.

Or, in the case of social media, looking at the specific steps a provider has taken to limit harassment and stop the posting of disturbing material.

More than just numbers

Clearly, financial metrics will always be an essential component of company research. In addition to these, though, by specifically including such vitally important non-financial information the goal is better investment decisions, better social responsibility and is also more effective risk identification and management.

It’s perhaps no coincidence that awareness of responsible investing has risen since the GFC – with many people now expecting the financial industry to act more fairly, consider wider non-financial issues in decision making, and engage with companies in order to improve behaviour and investment outcomes.

No investor wants to sink their money into a stock that’s worthy but ultimately worthless. ESG thus offers a sophisticated solution for investors for whom ‘added value’ isn’t just extra money.